Eastern Prickly Pear

Eastern Prickly Pear (Opuntia humifusa) is a cactus of eastern North America and it is the only cactus native to Connecticut. It is sometimes also known as Indian Fig or Devil's Tongue.

This cactus is only found in a limited number of locations throughout the state, owing to very specific habitat requirements and dispersal patterns that are only vaguely understood. Most often these cactus colonies are found along the coastal regions of Connecticut, but they can also be found in isolated locations on rocky inland ledges and forest glades.

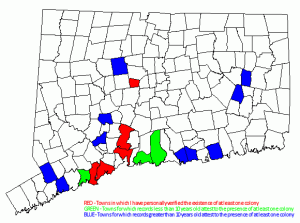

I have confirmed the existence of six (6) colonies and two (2) complexes of O. humifusa in eight towns in Connecticut: Bridgeport, Guilford, Hamden, Milford, New Haven, Old Saybrook, Plainville and Stratford. My research has revealed that further colonies can be found in Branford, Darien and Norwalk, however I have not yet personally verified the existence of these colonies. Historic records suggest that O. humifusa colonies also existed in Beacon Falls, Burlington, Franklin, Naugatuck, Oxford, Scotland, Seymour and Wilton at one time. However, because many of these records are over 100 years old, the colonies to which they refer may no longer exist. For example, extensive explorations of Beacon Falls have yet to reveal the continued of existence of O. humifusa which was known to be common there in the late 19th-century.

Distribution in Connecticut[edit]

O. humifusa is extraordinarily fragmented in its distribution throughout the state, even in coastal regions where the concentration is highest. This generally characterizes the species throughout all of its range in the Northeast United States. Even as early as 1900, for example, an issue of Popular Science magazine erroneously speculated that three colonies of O. humifusa found growing on Hook Mountain in New York might be "either the descendants of a stray from cultivation or, perhaps, purposely planted there by some enthusiast".[1]

In most Connecticut towns where I have confirmed the presence of O. humifusa, the colonies are found only in very isolated locations despite the fact that they are in close proximity to similarly suitable habitat. For this reason, it seems highly probable that O. humifusa living in Connecticut are not especially adept at long-distance seed dispersal, instead relying largely upon vegetative reproductive techniques which promote colony health in the immediate vicinity but accomplish little in the way of range expansion.

Habitat in Connecticut[edit]

Although many species in the Opuntia genus have been widely and thoroughly studied throughout the world, much of this research applies only loosely to Connecticut populations of Opuntia humifusa. O. humifusa is exceptionally unique in its ability to live and grow much further north than the vast majority of other Opuntia spp. It possesses a number of special adaptations that allow it to thrive in Connecticut's environment such as, for example, an unusually high tolerance to freezing temperatures. These unique adaptations contribute to habits which are unique to O. humifusa and, in some cases, differ significantly from other Opuntia spp.

However, the situation is made even more complex by the fact that the far northern extent of O. humifusa's range in New England begins to taper off in Northern Connecticut. In other words, Connecticut represents transitional territory, from rather suitable habitat along the southern coast to entirely unsuitable (or nearly unsuitable) habitat in the far north. Because the range extent of O. humifusa tapers off within Connecticut, we are likely to see a number of peculiarities in Connecticut's populations that derive from the fact that some environmental needs are only barely being satisfied by available habitat and conditions.

O. humifusa can be found in two distinct types of habitats within Connecticut: 1) low-elevation, coastal, sandy scrubland and 2) mid- to high-elevation, inland rocky ridges. For as much as these two habitat types are outwardly different, they generally offer very similar climate conditions. Both habitats typically possess a yearly average temperature which is slightly higher than that of Connecticut as whole, they offer extended exposure to full sunlight, and are both xeric habitats that possess dry, well-drained substrate.

O. humifusa only persists in locations where several hours of exposure to direct sunlight can be obtained on a daily basis. A study of O. humifusa colonies in Ohio, for example, found that the cacti ceased to flower when subjected to shade by recent encroaching tree growth.[2] As such, the absence of shade trees and dense, fast-growing shrubs in the immediate vicinity of the O. humifusa colony is imperative to its health and continued existence. Thus, not all coastal scrubland or rocky ridges necessarily provide sufficient habitat.

Northern Range Limit[edit]

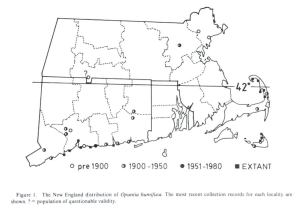

An evaluation of documented Opuntia humifusa colonies of New England and the Northern-Central United States (from earliest records to 1987) has demonstrated that the northern range limit of the species is approximately 42° N latitude.[3] There are a few reports of O. humifusa found living north of this line of latitude, but such reports are scarce and possibly erroneous, either representing populations introduced by humans or misidentification of other, more-northerly cactus species for O. humifusa.

The proposed northern range limit of 42° N runs just south of Connecticut's northern border, such that the state contains a transitional region where O. humifusa thrives along the southern coastline but is almost never found in the northern half of the state.

Temperature[edit]

Because temperature is widely acknowledged as a major factor in the ability of O. humifusa to establish itself in a particular locale, it is instructive to examine the location of known Connecticut colonies in juxtaposition with the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Zone Map of Connecticut. The USDA Zones Map shades various areas of the state based upon average extreme minimum temperature.

Zone 7a is warmest in Connecticut, with mean minimum temperatures of between 0°F and 5°F. The range of this zone in Connecticut is very limited, extending in a narrow band along western coastal regions of the state, as well as the farthest eastern coastline. Approximately 42% of the O. humifusa colonies I have observed (3 of 7 colonies) fall within Zone 7a.

Zone 6b covers most of the southern half of Connecticut and is characterized by a mean minimum temperature of between -5°F and 0°F. Approximately 42% of the O. humifusa colonies I have observed (3 of 7 colonies) can be found in Zone 6b.

Zone 6a covers most of the northern half of Connecticut, with the exception of the northwestern corner of the state. Mean minimum temperatures in the zone range from -10°F to -5°F. Only one colony, the Metacomet Colony in Plainville, falls within this zone.

Zone 5b represents the coldest regions of Connecticut, with mean minimum temperatures ranging from -15°F to -10°F. Only the northwestern hills of Connecticut fall within this coldest zone. I have not documented any colonies within this zone, nor have I found any historic data suggesting that O. humifusa ever lived there.

Although confirmed colonies of O. humifusa can be found in 3 of the 4 zones of Connecticut, the cactus clearly shows a preference for Zone 7a and 6b. Currently, 85% of the colonies I have photo-documented grow within these adjacent zones. Furthermore, if we include known colonies that I have yet to document, that number can likely be raised even higher, with as much as 90% - 95% of Connecticut's total biomass of O. humifusa growing within Zones 7a and 6b.

Coastal Sand Dunes[edit]

Historically, coastal towns of Connecticut have always harbored the majority of Connecticut's O. humifusa colonies. Although coastal areas of Connecticut still possess the greatest concentration of O. humifusa, it is believed that "development of coastal habitats has probably extirpated all but a select few populations in Connecticut."[3] Thus, over the last 150 years, O. humifusa has experienced a widespread decline in population throughout this historic coastal stronghold.

In my research, "coastal colonies" are defined as those colonies living no more than 1000 feet from Long Island Sound (this category also includes those colonies of O. humifusa found on islands off the coast of Connecticut). Any colonies living in Connecticut north of this boundary are considered "inland colonies" for the purposes of my research. Typically, "coastal colonies" are found at elevations not exceeding 40 feet above mean sea level (AMSL), though strictly speaking, elevation is not a determining factor in their categorization as "coastal" and some coastal colonies may occur at higher elevations.

Habitat Requirements[edit]

Substrate Stability[edit]

A study was performed in Canada's Point Pelee National Park in which juvenile O. humifusa cacti were planted on a sandy beach and monitored to determine the suitability of that habitat for use during future restoration projects. This study revealed what may be the most important limiting factor in the viability of sandy, coastal regions as long-term humifusa habitat. It was determined that "sand burial took a toll in terms of survival and plant size" and that O. humifusa "may not tolerate disturbance in mobile sandy substrates".[4] The study later goes on to state that "their numbers declined such that there would be no survivors after 2-3 more years, if the current rate of mortality continued" and that "self-sustaining populations could not be established...since transplants would not live long enough to reach sufficient size to flower and bear fruit." [4]

The results of this study do not indicate that all sandy coastal habitats are unsuitable as O. humifusa habitat. Indeed, the colonies present at Milford and Stratford, Connecticut are evidence to the contrary. Instead, the study helps us to distinguish suitable coastal habitat from unsuitable habitat. We can conclude that the ability of a given sandy coastal area in Connecticut to provide suitable, long-term habitat for O. humifusa cacti is likely to hinge upon the substrate stability of the site. Any factor which could lead to intermittent, partial burial of the cacti by sand, such as frequent flooding or unobstructed wind, would only serve to weaken the plants. In other words, classic sand dunes and other sandy coastal areas which are mostly devoid of plant life and subject to episodic disturbance by wind or water are unsuitable O. humifusa habitat, while stable-substrate, erosion-resistant, sandy coastal scrubland offers suitable habitat.

The O. humifusa colonies observed at Milford (Milford Point Colony) and Stratford, Connecticut (Short Beach Colony) seem to support this claim. For instance, it seems counter-intuitive that O. humifusa would be found interspersed throughout the sand alongside taller trees and shrubs which would undoubtedly serve to reduce the length of time during which full, unobstructed sunlight is available. However, it may well be that these trees and shrubs provide crucial substrate stability both by acting as a windbreak and due to the fact that the accompanying network of roots affords an added measure of erosion resistance.

Substrate Salinity & Salt Spray[edit]

Because coastal colonies of O. humifusa grow upon habitat which may possess exceptionally high levels of dissolved salts (as well as be subject to occasional flooding by saltwater), it is of interest to explore how coastal specimens deal with excess salts. It has been observed that colonies of O. humifusa living in the immediate vicinity of the seashore "accumulated more Na+ in their cladodes and appeared to be better adapted to aerial salt spray as well as episodal high salinity in the root medium than inland individuals".[5] Thus, O. humifusa is accommodating of high-salinity, even developing certain tolerances to high levels of dissolved salts which aren't possessed by cacti of the same species from inland colonies.

Inland Rocky Ridges[edit]

Even as early as the mid-1800s, it was observed by botanists that O. humifusa colonies were very fragmented in their inland distribution. I would estimate, based upon historic records and my own field examinations of extant colonies, that there may be as many as a dozen inland colonies in the state, perhaps less. I have thus far confirmed only five inland colonies in four towns (Hamden, New Haven, Old Saybrook and Plainville), though my research has revealed that at least eight inland towns in Connecticut were historically known to host wild O. humifusa colonies.

Indeed, research reveals that O. humifusa colonies on rocky or sandy inland habitats were once much more common than they are today. In all likelihood, many inland colonies have been lost to the natural process of forest succession whereby areas that were cleared for timber or previously maintained as open pastures are abandoned (generally between 1650 and 1850) and recolonized, first by shrubs and pioneer trees and eventually by thick forest. Since O. humifusa requires full sunlight, a good number of colonies are likely to have perished as the forest regenerated and shaded them out.

In my research, "inland colonies" are defined as those colonies living on the mainland that are more than 1000 feet from Long Island Sound. This category also includes those colonies of O. humifusa that may be found nearby inland riparian habitats. Any colonies living further south than this boundary are considered "coastal colonies" for the purposes of my research. Typically, "inland colonies" are discovered at elevations no less than 100 feet AMSL, though elevation is not a determining factor in their categorization as "inland" colonies and it is possible that inland colonies may be found at lower elevations.

Habitat Requirements[edit]

Soil & Geology[edit]

| Overview of Soil Characteristics of Inland O. humifusa Habitats | |

|---|---|

| Soil Characteristic | Description |

| Soil Type | 80% : Holyoke-Rock Outcrop Complex (Soil Type 78) 20% : Charlton-Chatfield Complex (Soil Type 73) |

| Soil Slope Types | 60% : 3 to 15 percent slope (Soil Type 78C) 40% : 15 to 45 percent slope (Soil Types 78E & 73E) |

| Soil Drainage | 100% : Well-drained |

| Soil/Bedrock Reactivity | 100% : Extremely acidic to moderately acidic |

| Soil Composition | 100% : loam over glacial till deposits |

| Bedrock Composition | 60% : (1) diabase, (2) basalt, (3) gabbro 20% : (1) basalt, (2) gabbro 20% : (1) gneiss, (2) granite, (3) schist |

Approximately 80% of the inland O. humifusa colonies that I have thus far discovered are found upon terrain with a soil type described as Holyoke-Rock Outcrop Complex (Soil Type 78) by the Soil Survey of the State of Connecticut (SSSCT) produced by the United States Department of Agriculture and the Natural Resources Conservation Service. Of that 80%, approximately 75% of those colony areas can further be sub-classified as exhibiting a 3 to 15 percent slope (Soil Type 78C). The West Rock Shephard Colony of Hamden was found on terrain that is classified as having a 15 to 45 percent slope (Soil Type 78E), however the colony location is very close to the transition line between soil types 78C and 78E and is therefore not a significant outlier. Thus, it can be stated that inland Connecticut O. humifusa colonies occur frequently on Holyoke-Rock Outcrop Complex with a slope between 3 and 45 degrees (or a mean slope of approximately 19 degrees).

The SSSCT describes Holyoke-Rock Outcrop Complex (78C and 78E) as "gently sloping to strongly sloping", "bedrock-controlled" hills and ridges "on uplands" where the depth to bedrock does not generally exceed 20 inches. The parent material of these habitat areas includes "loamy eolian deposits over melt-out till derived from basalt and/or sandstone and shale". Of particular interest is the fact that the soil of Holyoke-Rock Outcrop Complex is typically well-drained and "extremely acidic to moderately acidic".[6]

Further analysis using the Connecticut Environmental Conditions Online (CTECO) GIS Map of Critical Habitats revealed that 60% of Connecticut's confirmed inland O. humifusa colonies are found on habitat that is designated as Subacidic Rocky Summit Outcrops (SubRSO). CTECO describes these habitat areas as "dry to xeric exposed summits, ledges and other outcrops", noting the geologic composition to be "primarily basalt and other mafic rocks", where vegetation is typically restricted to "low shrubs, grasses and herbs". [7] While the Metacomet Colony habitat is not identified as Critical Habitat SubRSO, the conditions I observed there are congruent with the habitat description and it is likely this area was incidentally neglected on the CTECO Critical Habitat GIS Map.

Approximately 60% of confirmed inland colonies are found upon West Rock Ridge in New Haven and Hamden, Connecticut on a bedrock type known as West Rock Dolerite (USGS Code Jwr). The Metacomet Colony in Plainville, Connecticut has a bedrock type defined as Holyoke Basalt (USGS Code Jho). However, basalt is the common thread between these two bedrock types, with Holyooke Basalt being comprised primarily of basalt with gabbro as a secondary rock type while West Rock Dolerite is primarily composed of diabase with basalt and gabbro as secondary and tertiary rock types. The reactivity of these bedrock types ranges from subacidic (in the case of Holyoke Basalt) to somewhat pH neutral (in the case of West Rock Dolerite).

All of these observations seem to suggest that O. humifusa is partial to acidic soil which is rich in diabase, basalt and gabbro. However, this conclusion was seriously challenged when I documented the Ingham Hill Colony of O. humifusa in Old Saybrook. The Ingham Hill Colony exists on soil defined as Charlton-Chatfield Complex (73E) (which contains a mix of granite, schist and gneiss) on a bedrock type defined as Monson Gneiss (USGS Code Omo). The discovery of this colony seriously undermined my previous conclusion that inland O. humifusa had a special affinity for traprock ridges and I have since withdrawn my theory that the species exhibited a unanimous preference for basalt.

Instead, it is now my belief that the frequency at which O. humifusa appears on traprock ridges is merely a reflection of the fact that traprock ridges are especially common in Connecticut. In many towns, the only sunny, exposed ledges are found upon these traprock ridges, so that O. humifusa simply has nowhere else to grow. I do not believe that O. humifusa has any special preference for basalt, but that the high rate of occurrence of O. humifusa on basalt ridges is merely incidental.

While O. humifusa may not have any strong preference for soil of a specific composition, there are nonetheless certain characteristics of soil that must be met in order for it to qualify as acceptable habitat for O. humifusa. Every inland colony thus far discovered has been found upon soil that is especially well-drained and which is classified as moderately acidic to extremely acidic. These soil characteristics are found at every O. humifusa colony site, including the unusual Ingham Hill Colony site.

Elevation[edit]

Prior to the discovery of the Ingham Hill Colony at Old Saybrook, there seemed to be sufficient evidence that inland colonies of O. humifusa preferred elevations of between 350 and 550 feet above mean sea level (AMSL). Since the discovery of the Ingham Hill Colony, though, this assertion has been seriosuly challenged and I no longer believe O. humifusa has any particular elevation preference.

With the exception of the Ingham Hill Colony, O. humifusa colonies upon inland ridges certainly present a tight correlation in elevation. The Metacomet Colony is at an elevation of ~399 feet AMSL, the West Rock South Colony is at ~429 feet AMSL and both of the northern West Rock colonies range in elevation from ~515 feet AMSL at their highest to ~425 feet AMSL at their lowest. These elevations are tightly clustered between 350 and 550 feet AMSL, which had hitherto lead me to believe that there was some advantageous quality to this range of elevations which O. humifusa preferred. However, this theory seriously failed to account for those coastal colonies of O. humifusa that are found at significantly lower elevations (rarely exceeding 30 feet AMSL). This fact was especially troubling when trying to determine some meaningful correlation between suitable O. humifusa habitat and elevation.

The discovery of the Ingham Hill Colony in Old Saybrook was particularly important, because the O. humifusa found growing there were at an elevation of roughly 145 feet AMSL. This is the only instance that I have thus far encountered in which O. humifusa could be found at a distinctly intermediate elevation, significantly lower than colonies found on traprock ridges but significantly higher than colonies found in coastal scrubland. Therefore, I have abandoned my previous suspicion that O. humifusa prefers elevations between 350 and 550 feet AMSL. Instead, I would submit that the frequency at which inland O. humifusa occurs at these elevations is simply a product of the terrain of Connecticut, where the rocky cliffs of basalt ridges are very commonly found at elevations between 300 and 600 feet AMSL.

The Ingham Hill Colony proved to be something of a missing link, bridging the previously enormous gap in elevation between coastal colonies and inland colonies.

Indicator Species[edit]

Taking into account all of Connecticut's Opuntia humifusa colonies which I have personally examined, there does not seem to be any single plant community which is especially indicative of the species. That is to say, when we compare flora associated with O. humifusa on coastal sites to the flora associated with the cactus on inland sites, there is very little correlation. It is instructive, then, to examine these two types of habitats separately.

Coastal Indicator Species[edit]

Coastal colonies can be found growing in scrubland with a relatively high diversity of plant life including herbaceous plants, shrubs and trees. All of these associate plants are typically found on warm, dry, sandy habitat along the coast. Thus, I have so far been unable to correlate any specific plant species to O. humifusa on coastal sites.

There is a very minor degree of correlation between coastal O. humifusa and coniferous trees. A field exploration of the Short Beach Colony in Stratford, Connecticut revealed O. humifusa growing amongst an unusually dense concentration of Toxicodendron radicans (Poison Ivy), though I do not have sufficient data at this point in time to believe that this association is anything more than incidental.

Inland Indicator Species[edit]

Inland colonies have demonstrated an undeniable association with Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana, a coniferous juniper known commonly as the Eastern Red Cedar. It would seem that the high-elevation inland habitat requirements for J. virginiana closely mirror those of Opuntia humifusa.

To be clear, it is not as if O. humifusa can be found growing among every high-elevation inland site where J. virginiana thrives. However, the strong association I've observed between these two species leads me to believe that wherever one does happen to find inland O. humifusa colonies, J. virginiana will be found in close association. In fact, when conducting preliminary examinations of satellite imagery prior to an inland field exploration, I oftentimes rule out those potential habitat areas where I cannot see the tell-tale treetops of J. virginiana.

Growth Habits[edit]

There are basically two distinguishable growth habits observed in Connecticut's O. humifusa: "individual plants" and "clonal clusters".

Individual O. humifusa plants are those which exhibit a distinct basal center. While individual plants are almost always smaller than clonal clusters, they tend to grow taller.

Clonal clusters are large patches of O. humifusa which lack a distinct basal center and which are all linked into the same root system. These clusters primarily result from the process of layering, whereby cladodes of a parent O. humifusa plant which contact the ground are able to grow roots of their own, producing a genetically-identical extension of the parent plant. In this way, an individual plant may eventually expand to cover an area between 5 and 30 square feet (or more in some instances).

These two growth habits are, for the most part, readily distinguishable in their most representative instances. However, in some cases, it can be difficult to distinguish whether or not a particular grouping of O. humifusa represents a clonal cluster or simply a series of individual plants growing close to each other.

Highly Variable Morphology[edit]

Opuntia humifusa exhibits a particularly variable phenotype and, for this reason, it has been given several different scientific names across its rather broad range in the Eastern United States and Canada. Over the years, several botanists found specimens of O. humifusa which, in one way or another, differed in appearance so drastically from those with which they were familiar that it seemed quite obvious that the new find must represent a different species. Today, most of these erroneous species have been rejected and are understood to be synonymous with O. humifusa.

Characteristics that can potentially vary from colony to colony, or even between nearby plants in the same colony, include the height of the plants, the prevailing growing habit, the shape of the cladodes, the thickness of the cladodes, the presence of spines or glochids or the lack thereof, the color of spines and glochids and the color the flowers.

Because almost every outward trait of the cactus can vary so significantly in appearance, it is possible to find two plants living in close proximity which appear as if they are indeed entirely different species. Typically, though, plants from two different colonies on two different habitat types (especially a cactus from a coastal colony as compared to a cactus from an inland colony) will exhibit the greatest divergence in appearance from each other. It has been suggested that, due to the fragmented distribution of O. humifusa on isolated swaths of habitat, each disjunct colony may possess unique genetic traits that differ from those found elsewhere.

Response to Insufficient Sunlight Exposure[edit]

While O. humifusa is known to be especially shade-intolerant, colonies can survive under conditions where daily exposure to direct sunlight is somewhat reduced. In these situations, the cladodes (pads) of O. humifusa will tend to grow longer and narrower as a result of a process known as etiolation. Etiolation occurs whenever an O. humifusa plant receives fewer hours of direct exposure to sunlight than preferred. The elongation of the cactus pads is an attempt of the cactus to "reach" towards sunlight, similar to the way in which flower species germinating in the shade will grow long, arching stems in an attempt to reach the sunlight.[8]

Wherever etiolation is observed in O. humifusa, the plant is not receiving an ideal amount of direct sunlight exposure. The Ingham Hill Colony and West Rock North Complex, for example, exhibit particularly long cladodes (shaped like an elongated ellipse) that are undoubtedly undergoing etiolation in an attempt reach toward sunny areas that aren't shaded out by larger trees. In contrast, the O. humifusa of the Long Beach Complex and Short Beach Colony generally have rather short cladodes which are occasionally almost circular in their profile, owing to the fact that they receive plenty of direct sunlight exposure and are not undergoing etiolation, at all.

Although etiolation is a symptom of insufficient habitat conditions, it is not known how long O. humifusa can persist under etiolation conditions. It is possible, though not verified, that a colony may persist for decades under reduced light conditions and possess a nearly permanent etiolated growth habit. However, under reduced-light conditions, O. humifusa has been observed to cease flowering[2], a scenario in which the colony will not be able expand rapidly or disperse beyond its clonal cluster.

Gauging Severity of Etiolation[edit]

Etiolation in O. humifusa results in cladodes that are much longer than they are wide. However, this length-to-width ratio cannot exclusively be used to judge the degree of etiolation of a given specimen. In certain cases, I have discovered specimens growing on warm, exposed sand dunes (receiving no less than 6-8 hours of unobstructed sunlight per day) which exhibit unusually long, skinny cladodes that cannot have occurred due to etiolation, but which must have resulted from some other combination of genetic and/or environmental factors.

Therefore, in determining if a given O. humifusa specimen with elongated cladodes is suffering from insufficient sunlight exposure, it is necessary to consider the conditions of its immediate habitat. Examples of instances in which I have discovered etiolated O. humifusa specimens are as follows:

- Cacti growing within a thick patch of coastal Rosa rugosa (Beach Rose). In this case, the cacti probably colonized the area before the arrival of R. rugosa, which would have quickly overtaken the cacti. In response, the "buried" cacti were growing especially long, rigid cladodes in an effort to hoist themselves towards sunlight. These cacti, which still seemed surprisingly healthy, had already exceeded what is typically thought of as the maximum height of this usually prostrate species.

- Cacti growing upon a tight, rocky glade within the forest. In the case of the Ingham Hill Colony in Old Saybrook, the O. humifusa are being gradually shaded out by encroaching canopy growth. These specimens all exhibit rather elongated cladodes, certainly indicative of etiolation due to the miniminal amount of sunlight exposure available.

In general, elongated cladode length on any given specimen should only be attributed to etiolation in those instances where the affected plant clearly cannot obtain 6 hours of relatively unobstructed sunlight per day.

Reproduction[edit]

O. humifusa can reproduce both vegetatively and by seed. It can also grow by the process of layering, which is not technically reproduction even though it may appear otherwise.

Reproduction by seed begins when an O. humifusa flower, which grows from a cladode, is pollinated. The pollinated flower then develops into a fruit, typically referred to as a "prickly pear", which contains viable seeds. In some cases, these fruits naturally fall off of the parent plant and may germinate on their own. In other cases, the prickly pear fruit is eaten by birds or mammals which cannot digest the seeds. In this way, viable seeds are distributed in the predator's dung, potentially very far from the parent plant. At least one study of O. humifusa found that seeds which passed through the digestive tract of an animal had a higher rate of germination than those that did not.[9]

Vegetative reproduction in O. humifusa occurs when a cladode (or a piece of a cladode) breaks free of a parent plant and takes root. In this way, the broken cladode produces a new plant which is genetically-identical to, but entirely independent of, the parent plant. O. humifusa reproduces rather effectively in this manner.

Clonal clusters of O. humifusa can be produced by a process known as layering, whereby cladodes of an individual plant droop to the ground and begin growing a satellite root system. Layering is an especially common phenomenon observed on rocky inland habitats in Connecticut and a single O. humifusa plant can grow to form a very large clonal mat that covers a dozen square feet or more. However, since layering occurs without the cladode breaking free of the parent plant, the extended root systems produced by layering are actually just extensions of the parent. Thus, layering is technically not a form of reproduction but a form of growth, whereby a single O. humifusa plant expands its size without actually reproducing.

On occasion, it may be difficult to distinguish a cluster of several, individual O. humifusa from a clonal cluster which actually represents a single individual.

Conservation Status[edit]

According to the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, Opuntia humifusa is listed as a species of "Special Concern" in Connecticut. [10] This status is most likely due to the fact that O. humifusa has a naturally restricted range within the state. However, at least one study of O. humifusa has determined that natural succession, whereby previously open swaths of land are colonized by shrubs and shade trees, can result in a corresponding decline in population.[2] I have observed this phenomenon first-hand in Old Saybrook, where the Ingham Hill Colony is in danger of being shaded out as the surrounding deciduous forest grows older and taller. Since very large areas of territory may possess only a handful of O. humifusa colonies, especially in the case of inland habitats, it is entirely possible for forest re-growth to cause local extinction.

Definition of Terms[edit]

While certain terms referring to Opuntia humifusa, such as cladode and glochid, are well-defined and universally agreed-upon, it is necessary to implement some terms which are decidedly less strictly defined or even invented in the course of my own research. These terms include descriptions of the varying growth habits of the cactus, as well as the criteria for evaluating colony structures.

An individual plant is defined as a specimen which strongly exhibits a distinct basal center. Typically, only one to two tightly grouped cladode "stalks" form the foundation of the plant.

A juvenile plant is defined as an individual plant which has less than 6 cladodes and does not yet appear to be able to produce flowers. In many cases, juvenile plants may possess only one cladode which may have grown from seed or from a cladode that broke free of a parent plant. Juvenile plants, however, can also possess a half-dozen small cladodes and be very close to a level of maturation where it may begin to flower. In either case, juvenile plants are always rather small and represent O. humifusa specimens which are undoubtedly young. Due to insufficient study of the species, as well as varying growth rates on different habitat, it is difficult to specify an approximate age range with juvenile plants. Therefore, status as a juvenile is strictly determined by cladode count and the apparent inability of the small specimen to produce flowers and fruits.

Clonal clusters are defined as clumps or mats of O. humifusa which do not exhibit a distinct basal center. These mats can be highly variable in size, ranging from 2 square feet to nearly 40 square feet. From a technical standpoint, the distinction between an individual plant and a clonal cluster can be deceiving, since clonal clusters essentially represent individual plants which simply exhibit a clumpy or mat-like growth habit, thus occasionally becoming very large while still possessing a single, integrated root system.

A colony is defined as an instance in which O. humifusa can be found growing in a specific geographical location. Typically, a colony exists in a small enough area that a single set of coordinates can sufficiently pinpoint the location. Colonies can can range in size from a single, large clonal cluster (West Rock South Colony) to several dozen individuals and/or clonal clusters scattered generously throughout an acre of land.

A complex is defined as series of colonies which, despite being observably distinct, exist in very close proximity to each other. Each distinct colony included a given complex should exist no more than 500 feet from at least one other colony in that complex. Thus, a complex can encompass only a few acres and include only two colonies (West Rock North Complex) or may encompass well over 100 acres and include over a dozen colonies (Long Beach Complex). In certain instances, it is sufficient for two colonies to be grouped into the same complex if there is even little more than one or two individual plants that lie between them at some intermediate point. For example, if Colony A and Colony B are 800 feet from each other, but a lone individual plant can be found growing at some intermediate point in between, then both colonies are considered to be part of the same complex.

I first considered defining something like a complex after discovering two distinct colonies on the northern end of West Rock Ridge in New Haven (formerly West Rock Dunbar Colony and West Rock Shepard Colony) which existed in such close proximity to each other that it might have been possible to mistake them for one continuous colony if one did not examine them at length. The concept became a necessity after I examined the area of Long Beach in Stratford and Bridgeport, where colonies could be found liberally distributed over the course of nearly a mile of peninsular beach and scrubland. In such a case, it would simply be impractical to attempt to affix a unique name to each colony found in such a densely populated area. In these instances, the introduction of the concept of the complex serves to simplify the naming process and identify an area where O. humifusa is more locally widespread than at an isolated colony.

Confirmed Colonies[edit]

Through field exploration, I have confirmed the existence of O. humifusa colonies in the following locations. Where applicable, GPS tracklogs and photographs are supplied.

Metacomet Colony (Plainville)[edit]

The Metacomet Colony is a relatively small colony of Opuntia humifusa that can be found on traprock ridge in Plainville, Connecticut near Pinnacle Hill. The colony derives its name from its close proximity to the Metacomet Trail, which runs within ten feet of the cacti.

Background Information[edit]

The general location of a colony of O. humifusa living in Connecticut was documented in an online article by Stephen Wood (creator of the website Connecticut Museum Quest) on October 6, 2007[11]. Wood reported finding these cacti along the Metacomet Trail in Plainville, Connecticut, however he did not supply a precise location. The article was accompanied by photographic evidence. Further research seems to suggest that this colony was known to at least a few individuals as early as 2005.

Exploration[edit]

April 15, 2012[edit]

On April 15, 2012, I conducted a field exploration along a section of the Metacomet Trail in Plainville that followed the same route taken by Wood during his 2007 hike. Within approximately 1/4-mile of hiking, I discovered a sandy, sun-baked ledge adjacent to the trail upon which there were several O. humifusa. In all likelihood, this colony is the same one that Wood documented five years earlier, owing to the apparent health of these cacti.

During that same field exploration, I carefully explored several other ledges (over the course of approximately 1.25 miles) which seemed to present a habitat similar to that of the ledge with the confirmed cactus colony. I was unable to document any further colonies of O. humifusa along the Metacomet Trail.

Status[edit]

My field exploration has identified a single ledge along the Plainville-section of the Metacomet Trail upon which a colony of O. humifusa currently lives. This colony is known to have existed for at least five years and seemed, upon examination, to be relatively healthy. Although many ledges with a similar habitat can be found along nearby stretches of the Metacomet Trail, my explorations have led me to conclude that there are no further colonies in the area.

Concerns About Preservation[edit]

The colony of O. humifusa identified along the Metacomet Trail is apparently healthy, but it is relatively small and confined to a single ledge that is easily accessible. Thus, the colony (and the very existence of O. humifusa in the area) is potentially subject to severe impact by natural or human disturbance such as wildfires, extreme weather conditions, incidental tree fall, foot traffic by hikers and unlawful specimen collection. Any one of these factors, or any combination of them, could weaken, deplete or destroy the cactus colony.

Colony Location and Statistics[edit]

The Metacomet Colony is located in Plainville, Connecticut at 41.672165° , -72.831497°.

- To view this location in Google Maps, click here.

- To download the GPS tracklog of this exploration (KML format), click here.

Pertinent statistics concerning the location include:

- Elevation of Colony: ~399 feet above sea level

- Surficial Geology: Basalt

- Habitat Type: Inland Cliffs/Mountain Peaks [12]

Milford Point Colony (Milford)[edit]

The Milford Point Colony is a large colony of Opuntia humifusa living within the Smith-Hubbell Wildlife Refuge, an 8-acre parcel of preserve land adjacent to the Audubon Coastal Center at Milford Point. The colony derives its name from the Audubon sanctuary (which, in turn, derives its name from a common term for the peninsula in Milford, Connecticut).

Background[edit]

On a website dedicated primarily to gardening with native plant species, an article about Opuntia humifusa briefly mentions that the cactus "grows naturally in Connecticut along the coast. You can see it at the Milford Point Coastal Audubon Center along the boardwalk."[13] Known formally as the Coastal Center at Milford Point, the preserve is owned and managed by the Connecticut Audubon Society and is comprised of an 8.4-acre protected barrier beach in Milford, Connecticut.[14]

Exploration[edit]

April 28, 2012[edit]

On April 28, 2012, I conducted a field exploration of the Audubon Coastal Center at Milford Point during which I explored the relatively small nature preserve for Opuntia humifusa which, based upon my previous research, were likely to found along the beach boardwalk. This exploration involved a very short walk from the parking area to the boardwalk, as well as a brief off-trail survey of the area in which the cacti were discovered. In total, my route covered approximately 0.29 miles.

Congruent with the claims discovered during my research, O. humifusa were visible from the short boardwalk which traverses a series of dunes and terminates at the seashore. In many cases, these plants were only one to two feet from the boardwalk, unobstructed by any railings.

Although the boardwalk offered access to a few cacti, it was clear that other cacti could be found deeper in the dunes which were obstructed from view by various trees and shrubs. In order to obtain a rough estimate of the total number of cacti on the property, I left the boardwalk and conducted a survey of all those portions of preserve which could reasonably be accessed by foot. In total, I was able count 19 individual O. humifusa spread out over an area of approximately 1/2 acre. Since my investigation of the dunes was not exhaustive, it is fair to say that my count is strictly a conservative estimate of the total cacti growing at Milford Point.

Status and Description[edit]

My field exploration of the Audubon Coastal Center at Milford Point has revealed that Opuntia humifusa are a "featured" attraction at this preserve. The colony of cacti is not only exceptionally easy to find, but the boardwalk that traverses the dune area seems to have been constructed, in part, with the specific intention of exposing preserve visitors to wild cacti.

The colony of O. humifusa on Milford Point covers approximately 1/2-acre and includes at least 19 plants, however the actual number of plants is likely to be at least 10% higher than this estimate. Most of these cacti were "individuals", which is to say that there were very few which had formed large clonal clusters.

These findings stand in stark contrast to those of the colonies that I have discovered on inland ridges, which are generally isolated to a very small area (less than 50 square feet) and tend to be centered upon a clonal cluster, with "individual" plants accounting for less than half of the bio-mass of each colony.

The cacti colony at Milford Point was interspersed amongst dune shrubs, short coniferous trees and a variety of herbaceous plants. In some cases, O. humifusa were found growing around the bases of trees and shrubs, while in other instances they were growing upon clearings in the dune with a certain margin of open sand between other plant life. This, again, stands in stark contrast to inland mountain sites, upon which O. humifusa grows in areas with an exceptionally low diversity of trees and plants.

Concerns About Preservation[edit]

Of all of the sites at which I have observed Opuntia humifusa, the Coastal Center at Milford Point offers the easiest access to these plants while at the same time providing the greatest level of protection.

While the cacti colonies in Plainville and New Haven are found upon state-owned property such as West Rock Ridge State Park and the Metacomet Trail, these parcels of land are very large and protective legislation is nearly impossible to routinely enforce.

The Audubon Coastal Center at Milford Point, while providing similar protective regulations, encompasses a very smaller parcel of land (less than 9 acres) upon which it is considerably more practical to conduct regular assessments of the colonies health. Thus, I am confident that the colony of O. humifusa at Milford are relatively safe under the protection and monitoring of Audubon Center staff.

Colony Location and Statistics[edit]

The Milford Point Colony is located in Milford, Connecticut at the Audubon Coastal Center at Milford Point. The coordinates of the colony within the Audubon Center are 41.175451° , -73.100733°.

- To view this location in Google Maps, click here.

- To download the GPS tracklog of this exploration (KML format), click here.

Pertinent statistics concerning the location include:

- Elevation of Colony: ~14 feet above sea level

- Surficial Geology: Sand (composed primarily of quartz)

- Habitat Type: Coastal Sand Dunes [12]

West Rock Colonies (New Haven & Hamden)[edit]

There are three colonies of Opuntia humifusa found within the boundaries of West Rock Ridge State Park, which extends south to New Haven and north to Hamden. The West Rock South Colony is located in the southern half of the park within New Haven. The West Rock North Complex is comprised of two colonies which are located in the far-northern end of the state park.

Geographic & Historic Overview[edit]

West Rock Ridge is a prominent traprock ridge in Connecticut that runs in a north-south direction, extending roughly 5 miles from Hamden to northern New Haven and skirting the borders of Woodbridge and Bethany along its western edges. Although West Rock Ridge is now almost entirely contained within the 1,800-acre West Rock Ridge State Park, this was not always the case. West Rock Ridge, as a protected parcel of land, began in 1826 as a small 50-acre city park in New Haven (along the southern end of the ridge). By 1975, the State of Connecticut had established West Rock Ridge State Park on areas of the ridge which were not owned by New Haven. By 1982, New Haven's city park on West Rock Ridge had grown to encompass roughly 600 acres of land, all of which was donated to the state that year to be incorporated into West Rock Ridge State Park. Further parcels of land were added to the state park whenever they became available, swelling the park grounds to the roughly 1,800 acres that it encompasses today.[15]

Background Information[edit]

Although plenty of records exist which suggest the presence of Opuntia humifusa on West Rock Ridge, very few of these records offer any specific information as to where the cactus can actually be discovered. This was of particular concern because West Rock Ridge State Park is over 5 miles long, extending from New Haven in the south to Hamden in the north (and even straddling the borders of Woodbridge and Bethany on its western edges). Launching precisely targeted explorations of West Rock Ridge required the extensive study of satellite imagery, which permitted me to focus upon those areas which are not heavily forested and, thus, have at least some measure of potential to be O. humifusa habitat.

The oldest evidence that I've thus far discovered which attests to the existence of Opuntia humifusa in New Haven, Connecticut dates to the mid-1800s. A Report on the Trees and Shrubs Growing Naturally in the Forests of Massachusetts, Volume 2, published in 1846, very briefly mentions that the O. humifusa "is said to be found at New Haven, in Connecticut."[16] No specific information is provided concerning the whereabouts of a colony.

In a modern written overview of West Rock Ridge in New Haven, Connecticut, the West Rock Ridge Park Association notes that the ridge offers an "extraordinary biodiversity of plants and animals from prickly pear cactuses to 230 species of birds".[17] The text does not offer any further mention of O. humifusa, nor does it offer photographic evidence.

Further supporting this claim, an article was published on the website of the Mycological Society of America which details a group hike throughout West Rock Ridge scheduled to take place in 2012 during the organization's annual meeting. Although the organisms of interest to mycologists are primarily mushrooms and other fungi, the article nonetheless states that hikers in the West Rock Ridge area "occasionally [find] prickly pear cactus".[18] No further mention of cacti is made in this article.

The compelling evidence of the presence of O. humifusa on West Rock Ridge comes in the form of a photograph taken by Michael Hornak in 2011. The image portrays O. humifusa in bloom and the geo-tag data pinpoints the location of the plant to be at the far northern end of West Rock Ridge State Park in Hamden, Connecticut.[19]

Exploration[edit]

A preliminary examination of satellite imagery of West Rock Ridge revealed several areas along the southern end of the park where habitat suitable for O. humifusa potentially existed. Because the southern end of the ridge has a greater concentration of areas that aren't covered with thick forest, my earliest exploration focused on this region. Exploration of the northern end of the ridge was conducted later after the discovery of Hornak's O. humifusa photograph.

April 28, 2012[edit]

I conducted a field exploration of the southern half of West Rock Ridge State Park on April 28, 2012, during which I carefully investigated all of the target areas in that region that were identified in my preliminary studies of satellite imagery. This entailed a hike of approximately 3.08 miles and the route variously included hiking on foot trails and along the park road. Extensive bush-whacking was required in order to explore all of the target locations, many of which were between 20 and 100 feet off of the road or established trails.

Target areas of exploration primarily included west-facing and south-facing ledges along the precipices of the southern half of West Rock Ridge. Most of these areas were devoid of trees or, at least, very sparsely forested. A thorough investigation of these target areas revealed no presence of Opuntia humifusa.

However, I did succeed in locating a healthy colony of cacti in an area which was not within my original list of target areas. The colony was located on a relatively small clearing within the forest towards the interior of the ridge. This clearing consisted of an isolated, slightly elevated dome of exposed bedrock which enjoyed full sunlight and supported a bare minimum of herbaceous plants. The colony included one large clonal cluster of cacti as well as a number of individual cacti along the outer perimeter of the clearing which were at various stages of maturation.

May 5, 2012[edit]

A second field exploration was conducted on May 5, 2012 and involved an investigation of approximately 1.09 miles on the far northern extent of West Rock Ridge in Hamden, Connecticut. This exploration revealed several areas, some quite large, where bedrock was exposed at the surface and there was a bare minimum of tree growth. However, most of these "obvious" areas yielded no findings. Eventually, I ventured to the steep, terraced precipices on the eastern side of the ridge and succeeded in discovering a large clonal colony of O. humifusa. I quickly noticed that this uppermost cluster was only the tip of the iceberg, as further clonal clusters could be seen growing on several lower ledges descending the face of the ridge.

After thoroughly documenting this colony, I began moving northwards and checking similar habitat for the presence of another colony. I succeeded in discovering another colony approximately 200 feet further north of the first. This colony shared a similar character with the nearby find, where a several clonal clusters could be found on successively lower-elevation ledges.

Status and Description[edit]

West Rock South Colony[edit]

My first field exploration identified a small, isolated, exposed patch of bedrock within the forest on the southern half of West Rock Ridge in New Haven, Connecticut upon which a colony of Opuntia humifusa currently lives. I have not found any explicit evidence that the location of this colony has been previously documented.

The colony, which I have named West Rock South Colony, consists of a large, clonal patch covering approximately 25 to 35 square feet. Within 5 to 10 feet of this clonal center were approximately 6 or 7 individual outlying "satellite" cacti.

There is a bare minimum of herbaceous plants on the cacti habitat, as would be expected. The most prominent additive feature of this colony is a large, gnarled, many-trunked juniper, specifically an Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana). The large clonal mass of cacti can be found tightly skirting the base of this tree.

West Rock North Complex[edit]

My second field exploration identified two very large colonies of Opuntia humifusa on the east-facing cliffs at the far northern end of West Rock Ridge in Hamden, Connecticut. These colonies are situated barely 200 feet from each other and are rather significant inland colonies in Connecticut, primarily for their striking demonstration of circumstances in which O. humifusa can effectively expand its range via barochory (gravity) as opposed to zoochory (animal-assisted seed dispersal). Although these two colonies were originally given separate names (West Rock Shepard Colony and West Rock Dunbar Colony), they were later collectively renamed the West Rock North Complex after changes to my naming conventions enacted in July 2012.

Both of these colonies exhibit a structure which is supremely demonstrative of a scenario in which O. humifusa can successfully colonize surrounding habitat. The uppermost clonal clusters of each colony are found at an elevation of roughly 500 feet. Interestingly, numerous further clonal clusters can be found immediately below on successive terraced ledges that extend as far as 50 to 100 feet down the face of the ridge. My observations suggest that the clonal clusters at the highest elevations are most likely the oldest, progenitor clusters and that, as cladodes and fruits broke free of these older plants, they would tumble down the face of the ridge. Whenever these disconnected cladodes or fruits came to rest on a lower ledge, they would take root or germinate and produce a new clonal cluster. Over a number of years then, these colonies became quite large and can be described as "cascading" down the face of the ridge.

I counted at least a dozen clonal clusters and as many as two dozen individual cacti in the southernmost of the two colonies. The northernmost has fewer individual plants but its clonal clusters, of which I counted roughly ten, tended to be larger. But the most impressive characteristic of this complex is the role which gravity has played in expanding the size of the colonies over time. Both of these colonies probably began as a single, high-elevation clonal cluster on the uppermost ledges of West Rock Ridge. With the help of gravity to carry broken cladodes and fruits to lower-elevation ridges, a process known as barochory, those two original colonies each expanded their mass by at least 1000%. Indeed, the West Rock North Complex offers a rare demonstration of just how remarkably effective O. humifusa can be in expanding its local range without the assistance of animals as intermediaries, at least so long as the terrain is such that gravity can be harnessed to widely distribute fruits and broken cladodes. No where else in Connecticut have I discovered a colony which clearly demonstrates the enormous potential of O. humifusa to harness barochory.

The West Rock North Complex was found in close association with Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana var. virginiana) just as the considerably smaller West Rock South Colony.

Concerns About Preservation[edit]

The West Rock South Colony of Opuntia humifusa (identified on the southern half of West Rock Ridge) is apparently healthy but, as is typical of inland colonies, it is relatively small and confined to a single rocky outcrop. Despite the fact that this colony is only about 60 feet off of the southern park road, it is unlikely that this colony is at risk of easy discovery. There aren't any parking areas within close range to the colony, meaning that park traffic is not likely stop in the immediate vicinity. In addition, there are no trails that lead to the rocky clearing, so hikers aren't likely to happen the colony. Thus, there is a bare minimum of concern about the preservation of the O. humifusa colony at this site and a high probability that it will persist well into the future.

The colonies of the West Rock North Complex (identified on the northern end of West Rock Ridge) are exceptionally healthy and quite large. Although hiking trails run within 40 or 50 feet of the clonal clusters at the highest elevations, the cacti would be difficult to spot unless one were expressly looking for them. Furthermore, the "cascading" quality of these colonies means that, even if harm were to come to the more accessible high-elevation clonal clusters, those clusters on the lower ledges would still flourish by virtue of their relative inaccessibility. There is little concern about the preservation of this O. humifusa complex.

Colony Locations and Statistics[edit]

West Rock South Colony[edit]

The West Rock South Colony is located in New Haven, Connecticut at West Rock Ridge State Park. The coordinates of the colony within the park are 41.335736° , -72.964300°.

- To view this location in Google Maps, click here.

- To download the GPS tracklog of this exploration (KML format), click here.

Pertinent statistics concerning the location include:

- Elevation of Colony: ~429 feet above sea level

- Surficial Geology: Unknown (likely Basalt)

- Habitat Type: Inland Cliffs/Mountain Peaks [12]

West Rock North Complex[edit]

The West Rock North Complex, comprised of two distinct colonies, is located in Hamden, Connecticut at West Rock Ridge State Park. The coordinates of the southernmost colony are 41.398765° , -72.945621°, while the coordinates of the northernmost colony are 41.398970°, -72.944514°.

- To view the location of the southernmost colony in Google Maps, click here.

- To view the location of the northernmost colony in Google Maps, click here.

Pertinent statistics concerning the location of the complex include:

- Elevation of Colony: Ranges from ~508 feet to ~430 feet above sea level

- Surficial Geology: Basalt

- Habitat Type: Inland Cliffs/Mountain Peaks [12]

Short Beach Colony (Stratford)[edit]

The Short Beach Colony is a large colony of Opuntia humifusa spread generously throughout about one to two acres of flat, sandy scrubland fronting Long Island Sound at Short Beach Park in Stratford, Connecticut. The colony is named after the beach park in which it was found.

Background[edit]

Unlike all of my other finds (as of May 2012), I had no prior research indicating the existence of Opuntia humifusa within Stratford's Short Beach Park. While my research did reveal that O. humifusa was known to live in Stratford, Short Beach Park was not among the known locations that I was able to dig up. Thus, when I decided to investigate this area, it was purely on a whim. I simply knew that O. humifusa was documented as living nearby (within only a mile or so along similar beachfront land), so I thought that I might investigate.

Exploration[edit]

May 9, 2012[edit]

On May 9, 2012, I conducted a field exploration of Short Beach Park in which I focused exclusively upon a swath of sandy scrubland found within. This exploration involved roughly 1/2-mile of walking in total, during which I attempted investigate all of the potential habitat areas in the immediate vicinity.

Although I uncovered no material in my research which suggested the presence of Opuntia humifusa at Short Beach Park, I was surprised to discover the first specimen within only a minute or two of searching. Subsequently, I discovered numerous other specimens spread out over roughly an acre.

These cacti are actually rather easy to find, which may seem odd considering that no literature, articles or photographs of them can be found online. There are probably three factors which contribute to this lack of publicity. First, Short Beach Park is generally open only to residents of Stratford, meaning that the park doesn't get nearly as many visitors as if it were open to surrounding towns. Second, those Stratford residents that do visit the park probably tend to be interested primarily in visiting the sand beaches, not the scrubland behind them. Finally, one of the most common herbaceous plants that I found in association with this colony was Toxicodendron radicans (Poison Ivy), a highly-allergenic plant which is readily identifiable and generally avoided at all costs by humans. Some combination of these three factors is responsible for the relative "secrecy" of this colony despite the fact that it is easily accessible and found in extremely close proximity to heavily-visited beachfront.

Nonetheless, there is a trail matrix weaving throughout the scrubland which I doubt is of natural origin, so there must be some measure of human tending/landscaping to the area, as well as at least some regular foot traffic. Thus, this colony is probably well-known locally, but simply hasn't been publicized for one reason or another.

Status and Description[edit]

My field exploration of Stratford's Short Beach Park has revealed a large colony of Opuntia humifusa growing on dry, sandy scrubland behind the sand beach. Despite being little-known throughout the state, this colony is probably rather well-known to those Stratford residents that frequent the park since it is easily accessed from high-traffic beach areas.

The Short Beach Colony contains specimens that are spread throughout an acre (or more) of land, with most specimens being at least 15 to 20 feet apart. I counted a total of 14 O. humifusa specimens: four (4) large specimens, five (5) small specimens and five (5) specimens of intermediate size. Although there is always some measure of inaccuracy with these counts, owing to the clonal growth habits of O. humifusa, this count is rather thorough.

Interestingly, there did not seem to be any significant clonal clusters at all, a finding which is congruent with the Milford Point Colony and which contrasts sharply with colony structures found on inland ridges. Although I did count four "large" O. humifusa specimens at Short Beach, these were relatively tall plants which, unlike clonal colonies that I've observed, still maintained a tight, individual structure with a discernible basal center.

The habitat area at Short Beach is exceptionally similar to the habitat area at Milford Point. At both of these habitat areas, the O. humifusa specimens are interspersed amongst dune shrubs and low-growing herbaceous plants along with a few coniferous trees, though the Short Beach habitat exhibited a lower density of coniferous trees and higher density of shrubs than the Milford Point habitat. Also congruent with Milford Point, O. humifusa did not seem to have a preference for any particular margin from larger shrubs; some specimens were found growing right at the base of shrubs, while others were found in more open, exposed areas amongst sparse, low-growing herbaceous plants.

The Short Beach Colony exhibited a similarly high diversity of associated plant life as the Milford Point Colony. At least one of those herbaceous associates was Toxicodendron radicans (Poison Ivy), which was exceptionally prevalent. However, because T. radicans can be found in a wide range of habitats where there are no cacti, it cannot yet be considered anything more than an incidental associate (that is, I do not yet consider T. radicans to be a useful indicator species).

Possibility of Human Introduction[edit]

Research into the history of Short Beach Park reveals that, as late as the early 1970s, there were numerous cottages there and the northeastern section of the park was being used as a town dump of sorts.[20] The last of the cottages were demolished in 1972 after the town emerged as the victor of a 15-year debate over whether the cottagers or the town held ownership over the land. At some point afterwards, between 1972 and 1973, Short Beach was developed as a town park.

Given these findings, there is some measure of question as to whether or not the O. humifusa that can be seen today at Short Beach were introduced by the park designers. On one hand, these cacti are on ideal habitat and would seem to be natural in origin. On the other hand, it is entirely possible that this habitat area did not exist prior to park development.

At this point, I do not possess enough information to make any conclusions in this regard.

Concerns About Preservation[edit]

Although the Short Beach Colony is easily accessible and in close proximity to areas that likely receive a good deal of foot traffic, I have minimal concerns about preservation. The plants are relatively inconspicuous unless you are looking for them and they seem to have fared very well thus far. I cannot think of any reason why this would change in the foreseeable future.

Colony Location and Statistics[edit]

The Short Beach Colony is located in Stratford, Connecticut at Short Beach Park. The colony is spread out over a large area (approximately one acre), so it is not possible to provide pinpoint coordinates that are sufficiently representative. Suffice to say, the westernmost O. humifusa specimen is located at 41.1638° , -73.1093°, while the easternmost specimen is located at 41.1648°, -73.1090°.

- To view the westernmost location in Google Maps, click here.

- No GPS track log was recorded for this exploration.

Pertinent statistics concerning the colony location include:

- Elevation of Colony: ~5 feet above sea level

- Surficial Geology: Sand (composed primarily of quartz)

- Habitat Type: Coastal Sand Dunes [12]

Ingham Hill Colony (Old Saybrook)[edit]

A single colony of Opuntia humifusa can be found on a rocky forest glade beside a powerline cut in northern Old Saybrook, Connecticut. There is no formal parking area for the powerline cut, but it can be accessed on foot through a row of trees on the western side of Essex Road (Rt 153) in Westbrook, Connecticut. To be clear, the O. humifusa colony is not on the powerline cut. Rather, it is roughly 200 feet south of the powerline cut in the nearby forest. The colony is named after a series of three, non-connected roads in the vicinity of the colony which are all peculiarly named Ingham Hill Road.

Background Information[edit]

The first document I discovered attesting to the existence of an Opuntia humifusa in Old Saybrook came in the form of a newspaper article published in the Shoreline Times on December 28, 2010. The article discussed an on-going controversy over the development of a golf course and residential homes within a coastal forest of nearly 1,000 acres (the only unbroken forest of that size left along Connecticut's coast), describing a recent walkthrough of the proposed areas of development. During the walkthrough, a "large patch of prickly pear cactus, indigenous to the area and listed as a plant of Special Concern...was found on the Westbrook site".[21]

Because the Shoreline Times article did not provide very specific location information, more research was in order. Initially, I was only able to turn up the minutes of an Old Saybrook Planning Commission meeting (January 5, 2011) which, despite referencing the presence of O. humifusa somewhere in the planned development area, still failed to provide specific location information.[22]

Research for this site continued sporadically over the course of three weeks, with other documents surfacing that made mention of O. humifusa without citing a specific location.

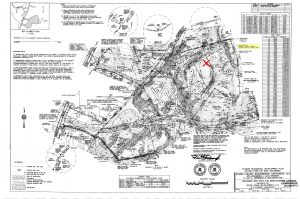

Finally, I discovered the website of the Alliance for Sound Area Planning (ASAP), an organization dedicated to the protection of the aforementioned 1,000-acre forest. As part of its mission to educate concerned citizens about the development project, ASAP offers a full compilation of all of the documentation related to the proposed development in Old Saybrook. Within the site plans for the development, the location of the O. humifusa colony is marked for the purpose of ensuring that the species is responsibly addressed during the proposed construction.[23] According to the map, the colony could be found about 0.5 miles west of Essex Road (Rt 153) within approximately 200 to 300 feet from a powerline cut in the forest.

Exploration[edit]

Although the ASAP-hosted map of the Old Saybrook development area does pinpoint the location of O. humifusa, the map itself is somewhat difficult to interpret due to the inclusion of planned roads that do not currently exist. Thus, an examination of satellite imagery was conducted to identify all of the rocky glades in the vicinity which could potentially serve as O. humifusa habitat. I found approximately five (5) glades that were worth exploring.

May 27, 2012[edit]

On May 27, 2012, I conducted a field exploration (~1.5-mile loop hike) of rocky forest in northern Old Saybrook. The forest was accessed on foot from Essex Road (Route 153) in Westbrook, Connecticut via a powerline cut. This exploration focused upon five (5) rocky glades within the forest, each within close range of the mapped colony of O. humifusa identified on proposed development plans for the area.

I succeeded in finding a colony of O. humifusa upon one of the five rocky glades previously identified. Surprisingly, other rocky glades which I had identified, and which offered similar habitat, yielded no further evidence of the presence of O. humifusa.

Status and Description[edit]

My field exploration in Old Saybrook revealed a single colony of O. humifusa living upon a rocky bald within a thick forest. Named the Ingham Hill Colony, it is comprised of what appears to be a single, large clonal cluster of approximately 20 to 30 square feet.

Associated herbaceous vegetation was restricted to sparse grasses and perhaps other inconspicuous low-growing plants. As with all inland O. humifusa colonies discovered (as of May 28, 2012), Juniperus virginiana (Eastern Red Cedar) was a close associate. The colony was essentially growing upon a rocky bald surrounded by a ring of J. virginiana.

In quite a few ways, the Ingham Hill Colony is of special importance to further understanding Connecticut's fragmented population of O. humifusa. The colony can be found growing at an elevation of approximately 140 to 150 feet AMSL. Previously, every colony I had documented was found either on coastal scrubland at an elevation between 5 and 15 feet AMSL, or upon rocky ridges at an elevation of between 330 and 550 feet AMSL. To date, the Ingham Hill Colony is the only colony I have observed at this intermediary elevation. This proves that my earlier deduction, that inland O. humifusa favors elevations from 350 to 550 feet AMSL, is not necessarily true.

In addition, the composition of the soil upon which the Ingham Hill Colony is growing is also quite exceptional in juxtaposition to all other previously-documented inland colonies of O. humifusa. According to the Soil Survey of the Connecticut, the Ingham Hill Colony is growing upon Charlton-Chatfield Complex (Soil Type 73) which is sub-classified as "15 to 45 percent slopes, very rocky" (Soil Type 73E). This soil type, which is derived variously from granite, schist and gneiss, is a notable diversion from the Holyoke soils (Soil Type 78) upon which all other inland colonies of O. humifusa have been discovered, indicating that the cactus is not likely to have any particular affinity for soil derived from basalt, diabase and gabbro, as previously believed. However, this soil type does coincide with other habitat requirements of O. humifusa, being well-drained and "very strongly acid to moderately acid".

Concerns About Preservation[edit]

On one hand, the Ingham Hill Colony is guaranteed protection from potentially invasive development because its presence has been thoroughly documented during site surveys for a proposed golf course. This means that if any future development plans should come to pass, the Ingham Hill Colony will be responsibly handled and appropriated protected.

Unfortunately, the more serious problem faced by the O. humifusa of the Ingham Hill Colony is that of forest succession. Tall deciduous trees tightly crowd the perimeter of the rocky outcrop upon which the colony is growing. Assuming that these trees will continue to grow taller and fuller, extending branches into the gap in the canopy, they will inevitably shade out the O. humifusa, first rendering them incapable of flowering and eventually robbing them of sunlight altogether. This chain of events, should it occur, will serve to eliminate the Ingham Hill Colony in perhaps as little as 10 years.

Judging by the plentitude of stone walls on the forest floor, it is safe to say that the entire area of the modern forest was in use as pasture land until at least the late 1800s. The colony of O. humifusa likely appeared within a decade or two after the pasture was abandoned. At that time, the only trees in the immediate vicinity of the colony would have been the coniferous Juniperus virginiana (Eastern Red Cedar), known to be a hardy pioneer species. Because J. virginiana is relatively low-growing on rocky soils, these trees would have posed no serious threat to the sunlight requirements of O. humifusa. Aerial photography from 1934 shows that the area of the modern-day forest was, at that time, still a patchy scrubland which would've been quite conducive to O. humifusa. The vegetation of this scrubland habitat would've continued to thicken after the 1930s, though. In time, probably between the late 1940s and early 1960s, taller deciduous trees began to dominate the land. Currently, even the ring of J. virginiana surrounding the colony is being shaded out by the deciduous canopy which is nearly twice as tall and growing more dense each year.

Based upon my examination of many O. humifusa colonies in the state, and considering the decidedly shade-intolerant habit of O. humifusa, it is my belief that the Ingham Hill Colony is doomed to be shaded-out within the coming decade. To the best of my knowledge, the loss of the Ingham Hill Colony would represent the extirpation of O. humifusa in Old Saybrook. However, the plight of the Ingham Hill Colony also provides crucial insight into the severe decline of O. humifusa throughout the state since the early 1900s. In all likelihood, extinct colonies that were once known to live inland in towns such as Scotland and Burlington probably suffered the same fate as what seems to lie ahead of the Ingham Hill Colony. That is, those colonies initially grew upon old, rocky fields and pastures which initially provided excellent habitat for O. humifusa. In time, as succession took place turning pasture into meadow and meadow into forest, the O. humifusa would inevitably have been shaded-out and disappeared from the landscape altogether. For instance, tt is possible that the O. humifusa of the Ingham Hill Colony are the last remaining descendants from a colony which was once much larger and more wide-spread throughout the vicinity in past decades.

Colony Locations and Statistics[edit]

The Ingham Hill Colony is located in the northwestern section of Old Saybrook, Connecticut. The coordinates of the colony within the forest are 41.3072° , -72.4165°.

- To view this location in Google Maps, click here.

Pertinent statistics concerning the location include:

- Elevation of Colony: ~145 feet above sea level

- Soil Type: Charlton-Chatfield Complex, 15 to 45 degree slopes, very rocky (Soil Type 73E)

- Bedrock Geology: Monson Gneiss (Omo)

Westwoods Colony (Guilford)[edit]

Initial attempts at locating this colony of Opuntia humifusa proved both frustrating and futile, with roughly 3 miles of hiking throughout the terrain revealing no presence of the plant despite plenty of seemingly excellent habitat. However, armed with the foreknowledge that a colony was found there as late as 2010, I conducted a second exploration of Westwoods nearly two months later and was successful in documenting the largest inland colony of O. humifusa in the state.

Background Information[edit]

In a blog article on A Walk Across the Giant, the author related a story of his hike throughout West Woods in Guilford, Connecticut, noting that his hiking party came upon a large colony of Opuntia humifusa on a ledge beside power lines[24]. This article was published in September 2010 and includes photographic evidence of the find.

Preliminary Assessment[edit]

Initial examination of satellite imagery of Westwoods revealed no shortage of rocky terrain with minimal growth of shade trees. Many of these rocky balds, however, were clearly within a powerline cut that slices through the northern half of the woodlands. Because these power lines are most likely relatively recent in origin, it was unlikely that the cactus colony would be found there.